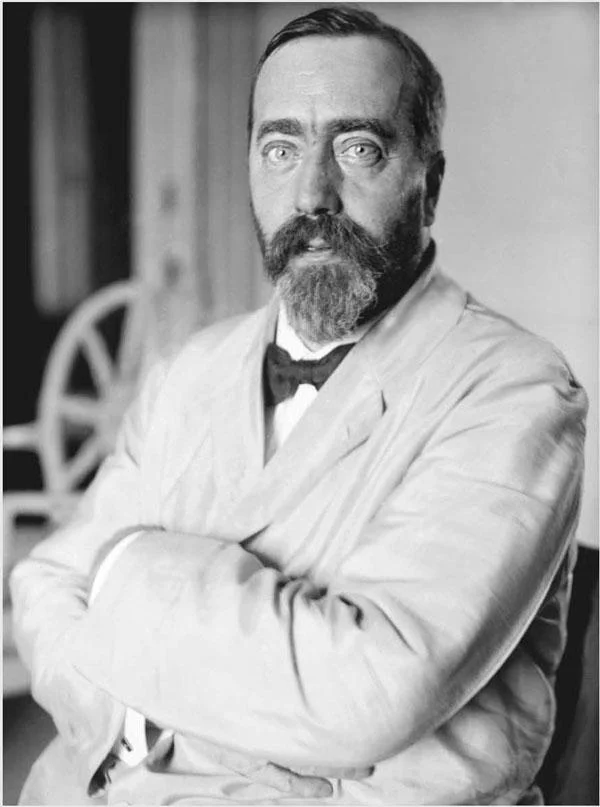

Bernhard Dernburg had given up his illustrious banking career to become Secretary of State for Colonial Affairs in 1907. The heavyset, full-bearded figure, with clear blue eyes, attentive, with a friendly disposition, portrayed raw power, intelligence, and decisiveness. Wildly successful as an innovative and daring reorganizer, the German banker had risen to stardom in German political and financial circles, en par with “Albert Ballin, Walther Rathenau, Max Warburg, Carl Fürstenberg, and Maximilian Harden.” The German Emperor had chosen this powerful Jewish banker specifically for the colonial secretary assignment because “[…] his distinguishing characteristic [was] Rücksichtslosigkeit, cold-blooded, unrelenting disregard for anything but his objective.”

Former Imperials Secretary of the Colonies and the highest ranking German official in the United States in 1915, Dr. Bernhard Dernburg.

Dernburg was looking for a new job in the summer of 1914. His political enemies, the legions of kowtowing Prussian bureaucrats the secretary had steamrolled throughout his career, had finally succeeded in having him fired from his cabinet post in 1910. It took the Emperor four years to find a suitable mission for his old friend who had used the forced break for extensive travels to Asia and touring on the lecture circuit.

The beginning of the Great War provided the opportunity. The former imperial secretary, the “Captain without a ship,” was to arrange for a large loan to the tune of $150 million in the United States and organize the sale of German war bonds on the American market. The proceeds were projected to finance the expected cost of purchases of American goods Germany needed in the war years. Nominally, Dernburg represented the German Red Cross in the United States, a designation causing great consternation when the American public found out that their donations financed the war effort instead of helping battlefield casualties. As a banker, Dernburg had been overseas on numerous occasions, and even spent his banking apprenticeship at Ladenburg, Thalmann and Co. in New York. He had also cultivated important contacts on Wall Street in his years as a banker, Colonial Secretary, and financier. He spoke excellent English. The imperial German government considered Dernburg an expert regarding the United States with the chutzpah to get things done. Unfortunately, much to the chagrin of Ambassador Count Bernstorff, diplomacy turned out not to be one of Dernburg’s strong points.

His first task was to raise a war loan for Germany in the United States, which he could not achieve in the face of a failing war effort in the fall of 1914. Dernburg then took over propaganda for Germany in the United States. Somewhat more successful, he gave interviews, wrote editorials and bombarded editors with prepared editorials. One of the targeted editors commented: “Our mail is dernburged until the postman can scarcely stagger up the front stoop with it. They are systematic those Germans. If you doubt it, send them your postoffice [sic] address.” The sinking of the Lusitania in May 1915 sank any chance of winning the hearts and minds of the American public. After a speech in Cleveland, defending the German atrocity which killed 129 Americans, Dernburg went back to Germany before the U.S. government would evict him.