The northwestern state contained fewer than three thousand Carrancista troops when Villa made his decision. The Villista governor, Maytorena, held most of the state with his forces made up of fierce Yaqui Indian fighters. Twelve thousand strong, a far cry from the proud army of forty thousand men of just a few months earlier, Villa’s Division of the North split forces. Approximately ten thousand soldiers set out across the Sierra Madre Occidental in the middle of October with only a few hundred left behind to defend positions in Chihuahua. Villa’s demoralized and spent army units wound their way through the valleys and passes of an extremely hostile environment without having the benefit of rail transportation through the mountains. In order to save food and increase speed the army left their soldaderas, who typically provided food, medical care, and logistical support, behind. Villa also could not take the cattle herds, which in the past had provided milk and food. Ox carts and donkey trains carried artillery and supplies through the unforgiving terrain.

The executioner, Rodolfo Fierro, himself one of the most brutal of Villa’s henchmen and a member of his inner-most circle, died on October 14, 1915 on the way across the Sierra Madre. He fell off his horse and drowned in a sinkhole with his soldiers idly standing by, watching the demise of their hated commander. Fierro had personally killed thousands of prisoners of war.

Villa’s first target was Agua Prieta, the Sonoran hamlet across Douglas, Arizona, a city of 20,000 souls with important smelters serving the mining industry. While Villa’s main force crossed the Sierra Madres, Villista General Urbalejo with a force of seven hundred took the border hamlet of Naco, Sonora. Another Villista detachment under General Beltrán took the copper city of Cananea. Beltrán and Urbalejo continued to march east, chasing the dislodged Carrancista troops commanded by Plutarco Elías Calles to the Agua Prieta garrison. The Villista forces in western Sonora combined with Villa’s main body of troops at the outskirts of Agua Prieta on October 30. Sommerfeld’s employee and head of the Villa munitions supply organization in El Paso, Sam Dreben, arrived in Douglas on the same day. He told State Department envoy George C. Carothers, “There was considerable ammunition being smuggled in the vicinity of El Paso.” These munitions seem to have come from stocks of the failed Huerta insurgency that Dreben now shipped to Villa, but that failed to reach him in time.

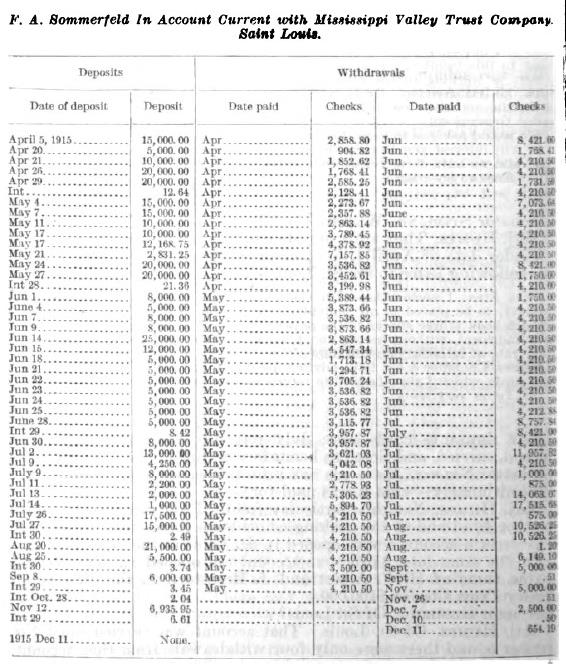

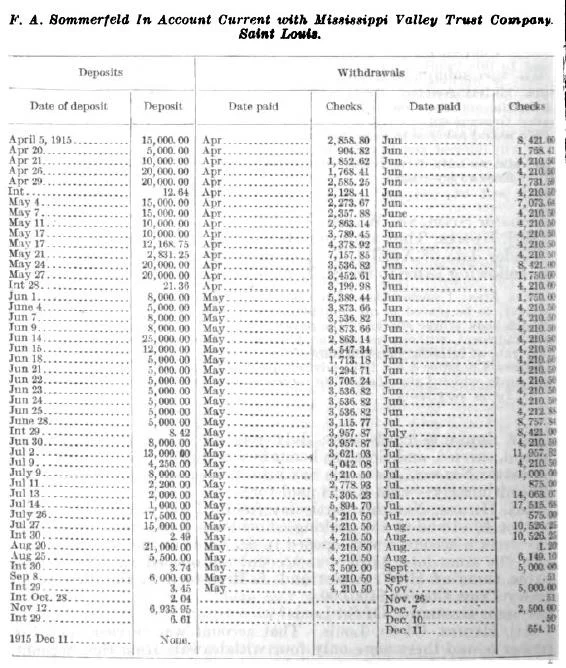

The tide had really turned against Villa. However, Dreben’s presence in Douglas, and the continued efforts to supply Villa with munitions, underlines the fact that Felix Sommerfeld remained one of the few supporters the Mexican revolutionary chief had left. Sommerfeld claimed to American authorities in 1918 that he had ceased all relations with Villa after Carranza had been recognized. That was a lie. He supported Villa throughout 1915 and 1916 to the detriment of the United States.

While Villa’s progress in the north seemed on schedule, Carrancista units under General Manuel M. Diéguez took the important port city of Guaymas in southern Sonora on October 13. Reinforcing his army from the sea, he marched north with twelve thousand troops. Hermosillo, the state capital in the center of Sonora, fell on October 20. The remaining Villista forces retreated northward, blocking the railroad for their Carrancista pursuers. The Carrancista forces dug in at Agua Prieta and, constructed long trenches. Machine gun emplacements and barbed wire secured the perimeter of the town. The mayor of Douglas desperately tried to get the U.S. army to prevent the impending battle on the American side of the border, fearing for the safety of his residents. Brigadier General Thomas F. Davis commanded the U.S. army forces securing the border. Davis had “three regiments of infantry, a regiment of field artillery, and several troops of cavalry” in a force of roughly six thousand men at his disposal.

Villa surveyed the battlefield. His scouts had estimated the opposing force to be somewhere between twelve hundred and three thousand. Despite the heavy defenses, minefields, barbed wire, and entrenchments, the Mexican general decided on a “softening” with artillery, then a frontal night attack with cavalry. He had used this strategy many times before. However, General Calles had learned his lesson. He was inspired by the European war, where trench warfare, minefields, and electrically charged barbed wire secured perimeters that were covered with machine gun emplacements and defended battle lines even against an overwhelming force. Villa only knew one way to attack, usually without even retaining reserves.

The Villista attack turned into a rout. The main charge around midnight failed to overrun the Carrancista trenches. Villa originally claimed, and stubbornly maintained, that U.S. forces provided the battlefield illumination. While the claim is still in debate, the power to run the lights as well as the electrification of the perimeter barbed wire, which claimed a few of his soldiers’ lives, most definitely came from the American side. The result was disastrous for Villa as the frontal cavalry attack ran up against the deadly machine gun positions. Villa ordered a total of five assaults on the enemy defenses and was repelled every time. Virtually no one managed to breach the trenches. Though Villa knew that there were more soldiers on the Carrancista side than he had originally expected, he did not adjust his strategy. General Calles had more than 7,500 men at his disposal, which he effectively brought to bear on Villa’s attacking force to the latter’s detriment. Also surprising for Villa was how well his opponents were armed. Calles had twenty-two cannon and sixty-five machine guns, a deadly long- and medium-range defense covering the entire depth of the battlefield. Train cars loaded with ammunition to re-supply the defenders waited on the American side of the border with U.S. soldiers providing security. Bodies, hundreds of dead, and even more wounded without the famous hospital train to care for them, littered the battlefield. He had failed, not only because of the formidable preparations and fortifications of the Agua Prieta garrison, but also because he had fought without a discernible strategy: No utilization of the element of surprise, no attack plan utilizing even the faintest hint of creativity, and the inexcusable lack of logistical support. It is questionable if under these circumstances an opposing force of three thousand or even less, which would have been the defending force without American aid, would not have been able to hold the town. Dislodging a well dug-in force, backed to the American border as a supply base, was virtually impossible, as General Maytorena had experienced in Naco ten months earlier.

Some historians and contemporary news reports have made much of the claim that Villa learned of the large reinforcements of the garrison only after the battle. As a matter of fact, on October 23, the U.S. government had allowed 4,500 reinforcements for Agua Prieta to travel via railroad through American territory. According to Hearst reporter John W. Roberts, Villa was completely unaware and surprised. “He saw me [on the American side of the border fence] and walked up quickly. ‘My God, Roberts, what happened?’… I told him in as few words possible [and] explained the situation. Villa said nothing… Just then, General [Frederick] Funston… rode up with a number of officers. I told Villa who he was. Villa merely stared. Funston dismounted and came forward. ‘Is this General Villa?’ he asked me, I nodded and introduced the two chiefs. Each stood in their own country and they shook hands over the barbed-wire fence.” John W. Roberts was a reporter prone to exaggeration. Villa had expelled him “as an obnoxious individual” from his territory because he published an interview that he had never given. The same seemed to be the case here. American newspapers reported on the transfer of Mexican soldiers through U.S. territory to Agua Prieta on October 25. The Villista governor of Sonora, Carlos Randall, officially launched a protest with the American State Department on October 30. That same day, Villa met up with the Yaqui contingents under General Urbalejo, who would have known all about this issue. According to historian Carl Cole who interviewed veterans of the battle, Villa had learned of the reinforcements for Agua Prieta that came via U.S. railroads two days before the battle. He simply failed to make adequate adjustments to his attack plan. It is also unlikely that it took an American reporter to introduce Villa to General Funston. If the general had wanted to see Villa, a U.S. army liaison officer would have contacted Villa’s staff or the other way around, as Funston indeed claimed.

Despite the disastrous attack strategy that cost Villa the last chance to re-kindle his military prowess in northern Mexico, the fact remained that the United States had actively intervened in the revolution. The Bureau of Investigations agent Steve Pinckney reported on November 2, “There is much ammunition in Douglas for General Calles, all of it being guarded by the local [U.S.] military authorities… The local railroad officials, express companies, and officers are working in harmony with the US authorities.” The U.S. Treasury Department reported to the Department of State on the day before the battle, October 30, 1915, “Collectors at Laredo, Texas and Nogales, Arizona instructed to facilitate movement of 1,000,000 rounds of ammunition for Carranza government to Agua Prieta.” Villa not only suffered from the arms embargo that gave Carranza advantage, but U.S. customs in El Paso also stopped all cattle imports from Chihuahua to the U.S. for “examination of brands.” Zach Lamar Cobb, the U.S. customs collector in El Paso, added coal to his list of items to be held up at the border.

Cobb was determined to do what he could to aid in the demise of the División Del Norte, despite serious threats from Villa’s people in the U.S. and instructions from Secretary McAdoo to refrain from his activities. Cobb, despite his official employment in the Treasury Department, was an agent of the State Department’s Intelligence Service. As such, he clearly executed the wishes of Robert Lansing, destroying what were the last remaining avenues for Villa to supply himself, and raise cash for munitions. Pancho Villa’s reaction to the aid his opponents had received from the U.S. government was remarkably measured on the surface. Known for violent outbursts of rage and emotionally charged decisions, the embattled Mexican general now weighed his options carefully. Villa initially talked openly about attacking the American side of the border. In response, General Funston moved his forces away from the border the day after the battle should Villa decide on shelling the town with his artillery. However, facing a combined American and Carrancista force of close to 14,000 troops, Villa only vented his anger but refrained from committing his remaining troops to a suicide mission. Instead, he took four Americans hostage and threatened to execute them. He released them a few days later. Villa retreated to Naco, Sonora, on November 4th, where his troops received a reprieve from the fight. His troops raided and pillaged Cananea on the way. The full weight of Carranza’s recognition as the de facto Mexican president seemed to finally sink in while resting at Naco. Agua Prieta had been a setup. The U.S. government had done everything in its power, short of engaging its own military, in an unprecedented move to make sure Villa would be defeated. According the special U.S. envoy George C. Carothers, who had been with Villa for the past years, the Mexican general appeared now “irresponsible and dangerous. He was subject to violent fits of temper and was capable of any extreme.”

After resting his troops in Naco and re-supplying, Villa decided to march on Hermosillo, the capital of Sonora. He attacked the defending force under General Diéguez head-on with close to six thousand troops. The once invincible general had to order retreat on November 22, again without the element of surprise, and with a force still reeling from the disastrous defeat at Agua Prieta. This time, the Yaqui Indian contingents defected to Carranza rather than volunteering as cannon fodder for the hapless Villa. In disarray, the Villistas made for the U.S. border city of Nogales. However, the American government had again allowed Carrancista troops to move through U.S. territory. Closing the border to prevent the Villa garrison from supplying itself, Nogales fell without much of a fight on November 25. Villa retreated into the Sierra Madre, however, not before engaging the 10th Cavalry and the 12th U.S. Infantry with sniper-fire, killing one U.S. soldier and wounding two. Bands of infuriated Villista cavalry rode up and down the border fence in Nogales challenging the U.S. military to come across for a fight. U.S. troops picked off several Mexican attackers but did not enter Mexican territory. Unable to fault himself for the tragic losses on the battlefield, Villa vented his frustration on the rural populations of Sonora. He personally commanded and participated in a horrible massacre, killing over sixty villagers in San Pedro de las Cuevas. The revolutionary chieftain crossed the mountains back into Chihuahua with less than a third of his original army to defend his last stronghold against the advancing armies of General Alvaro Obregón.

Read the rest of the story in Felix A. Sommerfeld and the Mexican Front in the Great War.