Update to the new book project: The single book for which I am working together with Charles H. Harris III, one of the greatest Mexican Revolution scholars alive, turned into a four-volume project. The title of the series is The federal Bureau of Investigation before Hoover. Volume 1, which is now available for sale as Kindle and paperback, is called The fBI and Mexican Revolutionists, 1908-1914. Volume 2, The fBI and German Intrigue, 1914-1917 will be available next year in May. We received great editorial reviews from the Wilson scholar and intelligence history giant Mark Benbow, the biographer of Abraham Gonzalez and Mexican Revolution scholar William Beezley, and Chicano Studies scholar Roberto Cantu. check the book out! It is the first thorough analysis of the early agents of the Justice Departments with lots of biographical information, amazing anecdotes and over 40 photographs.

This study covers a time (1908-1917) in the development of the federal Bureau of Investigation (BI) – renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) in 1935 - that arguably laid the foundation for the modern organization we know. Despite the over 100-year time difference, the book presents striking similarities between the BI operated in then and the FBI does now, especially with respect to political influence, counterintelligence challenges in an unstable world, and inter-agency rivalries. Founded as the result of a political disagreement between the Roosevelt administration and Congress in 1908, the BI evolved from a fledgling federal law enforcement agency to the premier intelligence and counterintelligence organization of the US government by 1917. The way the bureau enforced the neutrality laws had an impact on implementing American foreign policy.

Alexander Bruce Bielaski

The towering figure, largely ignored in the historiography, was A. Bruce Bielaski, the second chief of the BI (1912-1919). Bielaski steered the bureau through unprecedented growth, funding shortfalls, lack of trained personnel, with local courts, citizenry, politicians, and law enforcement agencies often sabotaging investigative and prosecutorial efforts. This study covers a period of significant challenges for the US: The Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) and World War I (1914-1918). Unrest in Mexico started in 1908 with the Flores Magón opposition to Porfirio Diaz violating US neutrality laws, progressed through the Madero presidency, military dictatorship, and violent civil war, to culminate in Pancho Villa’s attack on Columbus (1916) and U.S. military intervention. The BI and its leader Chief Bielaski met these massive challenges generally with success.

The study debunks the myth the BI amounted to little before J. Edgar Hoover took the helm in 1924 (Athan G. Theoharis with Tony G. Poveda, Susan Rosenfeld and Richard Gid Powers, The FBI: A Comprehensive Reference Guide from J. Edgar Hoover to the X-Files (New York: Checkmark Books, 2000)), that FBI counterintelligence started in the 1930s (Raymond J. Batvinis, The Origins of FBI Counterintelligence (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2007)), and that the BI before Hoover had lost its mission (Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones, The FBI: A History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007)). This study’s close look at the BI’s investigations into German intrigues clearly shows that despite one notable attempt to usurp the BI’s mission in 1915 (a rogue mission without presidential approval), the US Secret Service during World War I had no involvement in counterintelligence.

The book is a comprehensive analysis of declassified BI reports on Mexico. Where German intrigue intersected the story, BI reports on Germany are included. Complementing the BI source material are federal and local court records, Mexican foreign office and other government records, US State, Justice, and Military Intelligence Department records, German foreign office and war department records, private collections including from families of BI agents, newspaper and magazine articles, and secondary literature for comparative analysis. The audience for this 600-page study with over 2,000 footnotes will be largely academic.

This project started in 2008 with Louis R. Sadler and Charles H. Harris III sorting through the entire collection of RG 65 BI Old Mexican Files, which on microfilm is largely jumbled. After years of illness, Louis Sadler passed away in 2021 before the book could be written. To complete this project, Charles Harris partnered with Heribert von Feilitzsch. The book has approximately 250,000 words. A sequel is in the works.

The Jazz Age President: Defending Warren Harding by Ryan S. Walters (Washington D.C.: Regnery, 2022) – A review by Heribert von Feilitzsch

Published through an imprint of Salem Communications, a conglomerate of conservative and Christian media outlets, Walters prefaces his monograph as looking at the Harding presidency through a conservative lens. I appreciate the transparency. True to his word, Walters presents the 29th American president as a likable, hard-working, conservative patriot who in his short 2.5 years in office pulled the US economy out of recession (which Walters labels a “Depression”) and laid the groundwork for unprecedented economic growth that trickled down to the lowest rungs of the American wealth pyramid. According to the author, Harding laid the economic and financial tracks, on which his successor Calvin Coolidge continued. According to the author, President Wilson caused the 1919 “Depression,” Harding fixed it in a few months, and created unprecedented wealth that lasted for a decade. Herbert Hoover, the closet liberal (he calls him a progressive), without the necessary ideological foundation caused the Great Depression. What was Harding's ideological bedrock? “Putting America first.” (Chapter 7)

A spectacular show of historical acrobatics are the author’s efforts to spin away the well-documented corruption of the Harding administration that sold out American domestic and foreign policy to oil tycoons Harry Sinclair and Edward Doheny, and turned the burgeoning federal Bureau of Investigation into the administration’s fixer organization. While the author very superficially touches upon the Teapot Dome scandal that led to the prison sentence of Albert B. Fall, Harding’s Secretary of the Interior for accepting bribes, he contends that Harding had no idea and, when he found out, reacted responsibly. The opposite, of course, is the case. Harding personally signed papers that allowed Secretary Fall to lease oil rich navy properties to Doheny and Sinclair for a pittance. When Congress investigated the scandal in 1923, the FBI was so corrupted, that the US Secret Service was deputized to lead the investigations. The author mentions Gaston B. Means as a “former federal agent,” who is part of the cabal of authors and journalists maligning President Harding. As a matter of fact, the former German agent and conman had been hired as a Bureau of Investigation special agent during the Harding years. Head of the Bureau was Harding’s friend and fellow Ohioan William “Billy” Burns, who turned the federal agency into a cesspool of corruption. Means is a posterchild for the state of affairs of the Harding administration.

Walters’ lopsided story paints Woodrow Wilson a typical southern racist, while Harding was a “national healer,” who even pardoned his political opponent, the socialist Eugene Debs, and invited him to the White House. A heartwarming anecdote if viewed out of context. The author makes no mention of the Ku Klux Klan, which reached its zenith of eight million members in 1923 and terrorized minorities across the entire country. The Harding administration’s Justice Department under the corrupt leadership of Harry Daugherty, Harding’s former campaign manager, not only sat idly by, but the administration also adopted the clan’s America First slogan.

To further the ideological argument, the author blows the recession of 1919 completely out of proportion and squarely blames the Wilson administration for causing it. Once again, no mention of the flu, decommissioning millions of army soldiers, and adjustment of the economy to peacetime, which are the main factors of the brief economic downturn. Rather than Harding solely and single handedly saving the economy, the United States economy boomed as it collected on its wartime loans and supplied the utterly destroyed Europe with its products. The author’s lack of research and understanding of the historical environment show in painful mistakes, such as the Punitive Expedition to punish Pancho Villa for attacking Columbus, New Mexico in 1916 lasting three years (which would have prevented the US to participate in World War I - the US ended the incursion after nine months), or the occupation of Veracruz, Mexico in 1914 lasting two days (it lasted seven months).

To call Walters’ book a revisionist history would be too kind. It is a misinformed, horribly researched propaganda piece that selectively hides or elevates aspects of US history between 1918 and 1929 to suit the “most maligned president in American history,” a title conservative media now accord to Donald Trump. Other than a few memoirs and newspaper articles, the book completely lacks primary sources. In a solid scholarly approach, a historian lets the research lead to a conclusion, that may revise earlier works and conclusions. In this case the conclusion led the research, if one can be so generous as to call the use of a select few memoirs “research.” In summary, this book is a hack job of the first order.

106 years after the disastrous attack on Columbus, New Mexico, of 400 to 500 villista raiders, the reasons for the attack remain murky. Countless historians published countless accounts trying to piece together the facts and determine the motivation of Pancho Villa to attack the United States.

Here are the indisputable facts:

Pancho Villa risked his very existence with this attack. He lost twenty-five percent of his troops, and he would not play a significant role in the Mexican Revolution after his attack.

The remnants of the Commercial Hotel in Columbus

The Mexican raiders were looking for the proprietor of the local hardware store, Sam Ravel, but they also were looking for the manager of the bank, and hotel owners. Ravel happened to be in El Paso for a dentist appointment. Villistas sought out the owner of the Commercial Hotel , W. T. Ritchie, and killed him with five others staying at the hotel that fateful morning. James T. Dean, the owner of the local grocery store also died in the attack.

Sam Ravel

Villa stated that he wanted to “save Mexico’s sovereignty” after he suspected that Carranza had “sold out to the Americans.”

After the attack, rumors of why Villa had targeted the sleepy, insignificant border town of Columbus for this attack, ran rampant. We know today that Villa initially contemplated attacking El Paso to make his point, but in view of his decimated forces, decided on a smaller, less risky target. Villa stated that he considered the United States an enemy after Carranza was recognized as the “de-facto” government of Mexico in the fall of 1915. The Wilson administration had then clamped down on his supply lines, causing the defeat of Villa’s famed Division of the North. There are also lots of indications that Villa was influenced by the German naval intelligence agent Felix Sommerfeld to initiate an attack on the United States.

The most discredited view of why Villa attacked Columbus is the theory that Sam Ravel, the Jewish co-proprietor of the local merchant house, incurred the ire of the Mexican revolutionary and thus was the reason for Villa’s attack. As the theory proclaims, Ravel may have sold Villa bad ammunition, or somehow cheated him. To this day, no evidence has emerged to support this thesis. The grandson of the Columbus grocer James Dean, Richard Dean, had obtained Ravel’s sales records, which showed that the merchant had not sold any ammunition to the villistas since 1914 (when Villa was a member of the Constitutionalist forces). Canvassing 70,000 pages of bureau of investigation records dealing with neutrality law violations and smuggling during the Mexican Revolution, I did not find a single report that mentioned Sam Ravel or his merchant house. These investigative files identified and covered every person and business between 1910 and 1922 that had dealings with Mexican revolutionaries. Even if one would take the view that almost everybody at the border engaged in some sort of profiteering from the revolution, there can be no doubt that Ravel played an insignificant role in the activities. The big dealers Villa could have targeted were Shelton-Payne, Krakauer Zork and Moye, and Hayman Krupp, all of whom likely had sold bad ammunition at times.

The store of the Ravel Brothers

So, why does the Sam Ravel story persist? The question of why the raiders were searching for Sam Ravel (as they were searching for other residents), appeared first in the immediate aftermath of the Columbus raid. Residents tried to make sense of the disaster. Blaming the only Jewish family in town seemed like a reasonable proposition. Although this thesis clearly is rooted in anti-Semitism, it persisted over the decades, with “historians” perpetuating the lie that Ravel had “cheated” Villa and thus caused his wrath. Taking the claim at face value, it is preposterous. Villa had agents in every border community along the border. Had he really wanted to punish, even assassinate Ravel, he would have had that done without causing a huge international incident. Why would he have risked the destruction of his remaining forces for a business dispute? Villa’s horizon was much wider, as his lieutenants testified to, he was out to save his nation, his legacy, and defeat American colonialism.

Sadly, as we commemorate the 106 anniversary of Villa’s raid on Columbus, and as we try to heal, four generations removed from the event, the anti-Semitic trope of Ravel being the cause of Villa’s attack is promoted in new films promoted by Max Grossman, Cindy Medina, and Stacey Ravel Abarbanel, a descendent of the Ravel family no less, against all evidence, historical scholarship, and common sense. It is time to lay to rest the soul of a victim, who not only lost his business, but who is also the victim of racist persecution, Sam Ravel. RIP, Sam!

106 years ago this week, El Paso was in the throngs of a race riot, state of emergency, curfew, with U.S. infantry guarding the closed border, searching houses for rioters, and controlling streets of the city. What had happened?

In a banquet honoring the victorious Constitutionalist government of Mexico over the forces of Pancho Villa on December 28, 1915, General Alvaro Obregon gave a speech to El Paso’s leaders of government, the military and commercial community. He declared the Villa faction eliminated as a threat and emphasized Constitutionalist control over Chihuahua. Important to his speech was the encouragement of mining engineers and other American businessmen to come back to Chihuahua and pick up their disrupted commerce. After all, mining, cattle ranching and farming in Chihuahua produced great profits for American entrepreneurs and equally precious income for the Mexican tax collectors along the border.

Thomas D. Edwards, US Consul in Cd. Juarez

Trusting Obregon’s guarantees, seconded by the American Consul in Cd. Juarez Thomas Edwards and the El Paso Tax Collector and intelligence agent Zach Lamar Cobb, ASARCO decided to send a group of 19 mining engineers and employees to Cusihuriachic in the mountains 100 miles to the East of Chihuahua to restart operations of the Cusi Mining Company there. The men received visas from the Mexican consul Andres Garcia and proceeded on their trip on January 10, 1916. Charles Watson, the general manager of the Cusi Mining Company had with him his dog Whiskers and $3,200 in cash (about $68,000 in today’s value) to pay outstanding salaries and wages. He declined a military escort in the hope that the train would not incur unwanted attention. That turned out to be a fateful miscalculation.

When the train pulled into the little hamlet of Santa Isabel to fill the water tanks, passengers noticed two armed men on horseback riding by the windows of the train and peering inside. Shortly thereafter they sped off. The train also continued its journey. Approximately eight kilometers from Santa Isabel, just rounding the corner of box canon, a derailed train blocked the track. When the Americans looked out, they saw heavily armed men coming down the sides of the mountain and behind the train. Thomas B. Holmes, the only American survivor described what happened next:

“Watson, after getting off, ran toward the river, Machatton [actually Richard P. McHatton of El Paso] and I followed. Machatton [sic] fell. I do not know whether he was killed then or stripped. Watson kept running, and they were still shooting at him when I turned and ran down grade, where I fell in some brush, probably 100 feet from the rear of the train. I lay there perfectly quiet and looked around and could see the Mexicans shooting in the direction in which Watson was running. I saw that they were not shooting at me, and, thinking they believed me already dead, I took a chance and crawled into some thicker bushes until I reached the bank of the stream [the Ysabel river]. I then made my way to a point probably 100 yards from the train. There I lay under the bank for half an hour and heard shoots by ones, twos [sic], and threes. I did not hear any sort of groans or yells or cries from our Americans…”

After Holmes made it back to El Paso the next day and it became clear what had happened, the city erupted into an uproar. The next day, on January 12, rescuers from El Paso with a military guard of the Constitutionalists recovered the bodies. They were badly mutilated, with multiple gun shot wounds, one victim even had his head blown off, and all but Watson were stripped of their clothes.

As the bodies arrived in El Paso on January 12, angry, white mobs started roaming the streets. In the Hotel Sheldon, the mob encountered the American Consul Edwards having a drink. They chased him down the street back to Cd. Juarez. Zach Cobb, another target of the crowd, managed to lay low. Police and city officials called for calm but the crowd increased with every hour of the day. The anger, calls for revenge and posses to hunt down the perpetrators of the murders created an explosive environment.

John J. Pershing, Commander of Ft. Bliss, 1915

Two soldiers from Fort Bliss created the spark that set off mayhem. Walking down the street in the Mexican barrio Chihuhuita got into a fight with several residents. The brawl caused more soldiers from Fort Bliss to head into town. The mob now was looking for blood. El Paso’s sheriff and police force were quickly overwhelmed. They asked General Pershing, commander of Ft. Bliss, to help. Within hours he declared a state of emergency, issued orders for curfew, and moved troops into the streets to take control of the situation. As residents of Cd. Juarez streamed across the international bridge to come to the aid of the embattled barrio residents, the military closed all crossings and isolated the barrios.

It took a whole other day to finally establish calm. Only a few people ended up arrested. Suspected Villista sympathizers, most notably Miguel Diaz de Lombardo, a longtime Mexican diplomat and Villa representative, were chased out of town. Police saved Jose Ines Salazar from a lynch mob. He spend a night in jail. The murderers of Santa Isabel got away, but not for long. Many were killed in the raid on Columbus, New Mexico two months later. The leader of the Santa Isabel massacre, Pablo Lopez was shot in both legs, caught by the Constitutionalists a few weeks later and executed in the summer of 1916.

Pablo Lopez on a crutch moments before his execution.

Listen to me on the El Paso History Radio Show with Jackson Polk and Melissa Sargent, January 15, 2022 where we discuss the Santa Isabel massacre: https://fb.watch/az0y4EoxgP/

After the highly acclaimed book Abraham Lincoln and Mexico, Michael Hogan has written another paradigm smashing book on US-Mexican relations. Using important primary and secondary sources, Hogan shines a bright light on a tireless Mexican ambassador to the United States and an American administration that viewed the French occupation of Mexico with great concern. Fighting a civil war, Lincoln was sympathetic yet hobbled by the demands of the war he intended to win. In this vacuum, civil organizations in the United States shared a sense of solidarity with the embattled Mexican State. Fund raisers, discharged union soldiers, and concerned citizens defending the tenets of the Monroe Doctrine organized and armed the American Legion of Honor and the colored troops to defend Mexico. Within a brief period those American troops came to the aid of the embattled Mexican president Juarez and helped oust the occupation forces from Mexico.

Not only is this story of US-Mexican military cooperation virtually unknown, but this is an important history that stands in stark contrast to current US-Mexican tensions. It is the story of a neighbor coming to the aid of another. Hogan does a brilliant job describing the key players in both countries, their personalities, motivations, accomplishments, and sacrifice. The book puts blood and flesh on these historical figures. A gripping read!

As soon as World War I started in August 1914, the Imperial German government dispatched a select group of agents to the United States. The group included Heinrich F. Albert, Dr. Bernhard Dernburg, and Dr. Hugo Schweitzer. Already in place in the United States were Franz von Papen, the German military attaché, and Karl Boy-Ed, his counterpart from the Imperial navy. These men had the task of conducting operations on U.S. soil against the Entente powers, England, France, and Russia.

One of Schweitzer’s principle clandestine assets was Dr. Walter Theodor Scheele, a pharmacologist and chemist, who, while working in the United States, also was on the payroll of the Imperial War Department since the 1890s. Scheele became the technical genius behind the German sabotage campaign in 1915 and 1916. His deadly inventions caused far more havoc among allied shipping and in American factories than previously thought. Discovered and indicted in absentia, Scheele fled from U.S. authorities to Cuba in 1916 but American law enforcement agents captured him in 1918. After intense debriefing the American government was able to turn the agent. He became instrumental for the American war effort in the end of the war and never served any time in prison. After the war, he never told his story; neither did any historians in the time since.

Born in Cologne, Germany, in March 1865, Scheele satisfied the mandatory military service duty in an artillery unit after graduating from high school. Discharged with the rank of first lieutenant of the reserves he studied chemistry at the universities of Bonn and Freiburg. As a member of a student fraternity he received the telltale “Schmiss” across the right cheek from fencing without protection. Around 1884, Scheele earned a doctorate in chemistry from the University of Freiburg. The young chemist remained active as a reserve officer and earned the rank of captain before he decided to come to the United States in 1890. The German army retained the scientist as an intelligence officer for $1,500 per year.

Dr. Walter T. Scheele, the German “Bomb Maker”

An American secret service agent described the chemist as “a quiet, reserved man, who is constantly in deep thought, and very preoccupied. He is an intensive smoker… The tone and demeanor of Mrs. Scheele is rather domineering, and it is apparent that she is ‘boss’ in their home.” Maybe this observation explained Scheele’s heavy drinking and smoking habits, even carrying a “pearl handle” side arm on his belt in public. Between 1912 and 1914 Scheele worked on projects for the Bayer Chemical Company with Dr. Hugo Schweitzer as chief executive. Bureau of Investigations agents who debriefed Scheele in 1918 alleged that between 1910 and 1914 he also worked on the creation of high power explosives for the German military.

The first major project designed to stop or hamper allied shipments from the United States started in the late fall of 1914. The British sea blockade posed a huge supply problem for Germany. Definitions of unconditional and conditional contraband not only included arms and ammunition, but also vital raw materials such as rubber, cotton, and oils. In his laboratory in Hoboken, New Jersey, Scheele had devised a process by which oils and lubricants could be solidified, packaged, and shipped falsely manifested as “artificial fertilizer.” The crafty doctor had also invented methods of producing artificial rubber and concealing it much the same way. “Ordinary Para rubber [is reduced] to a brown powder… The… rubber reduced to powder was exported as fertilizer… to continue with the reduction of rubber to powder, Dr. Scheele dissolves the rubber in benzene and then mixes [it] in a rotary drum with magnesium carbonate. To reconstitute the brown powder, the ‘fertilizer’ is treated with sulphuric [sic] acid, which forms magnesium sulphate [sic] ‘epsum salts’ [sic] and the rubber comes to the surface in a conglomerate mass… the process for reducing lubricating oil to a powder is similar…”

The Hoboken laboratory not only churned out blockade circumvention products. Scheele had also amassed an astonishing repertoire of formulating explosives, rapidly accelerating incendiary chemicals, and artillery missiles propelled by compressed air. Among other things he had experimented with rapid accelerants and timed incendiary devices that could be used on a tactical level. American investigators and later historians defined Dr. Scheele’s participation in the German sabotage campaign with the founding of a “fertilizer company,” the New Jersey Agricultural and Chemical Company of Bogota [New Jersey] in March 1915. As described earlier, the truth was that this eminent German chemist and spy devoted all his time and resources to the Fatherland as soon as the war began.

With a sabotage order from the German Admiralty dated January 6, 1915, Heinrich Albert and his colleagues proceeded in earnest to stop the production and shipment of war materials to the Entente powers. Von Papen, Albert, and Schweitzer decided to ask Scheele to propose ways to firebomb factories and sink allied ships. Sinking a ship with a bomb was a difficult undertaking. The explosives had to be close enough to the exterior hull and below the waterline to cause any significant damage. To create a leak large enough to sink a steamer the bomb had to be physically large, like the size of a suitcase or larger. An allied agent in New York described Scheele’s invention in his memoirs:

Scheele’s Cigar Bomb Design

The device was so simple that one cannot even call it ingenious. The literature of the First World War has named these infernal machines indifferently ‘pencil bombs’ and ‘cigar bombs.’ They looked externally like a cross between the two. Inside a copper disk bisected the bomb vertically. A chemical which has a rapid corrosive effect on copper filled the upper compartment. When it had eaten through the disk it came into contact with the chemical in the lower compartment. The combination produced instantly a flame as hot as a tiny fragment of the sun. The acid did not begin to work on the copper until one broke off a little knob at the upper end. Then it became a time-bomb, the time – from two days to a week – being regulated by the thickness or thinness of the copper disk.

Scheele had solved the issue of size. He also changed the target from a hard-to-destroy steel hull to setting the cargo on fire and relegated the complicated timing and firing mechanisms to the heap of outdated bomb building technology. The little bombs burnt so hot that the lead chamber melted in its entirety. Lead screws in the assembly made sure that the bombs left virtually no trace. Workers could easily hide the three inch devices in their clothes and casually drop them within the cargo they were stacking. The fire bombs worked especially well with cargoes of sugar, which when ignited developed such intense heat that it became very difficult to extinguish the resulting fire.

If purchases of the tell-tale lead pipes are an indication, Scheele seemed to have started working on the development of the cigar bombs in the middle of January 1915. A firm order to go ahead with the production came from Franz von Papen within weeks of the sabotage order of January 8, 1916 against ships and factories in the U.S. Albert paid Scheele $10,000 ($210,000 in today’s value) to cloak his laboratory behind a “fertilizer” company. Other disbursals from Albert coded as “artificial fertilizer” appear the accounts of von Papen. They totaled $20,067.64. Historians have misinterpreted these funds to have been designated to buy oil and fertilizer. While this money came through Otto Lemke, who was one of Albert’s trading partners, it financed the bomb making project. The payments from von Papen and Boy-Ed are not listed in Scheele’s bank accounts. Lemke and Oelrichs handled the purchasing and shipping for the chemist.

On March 17, two weeks after Albert provided $10,000 in seed money, von Papen reported to his superiors in Germany in code, “Regrettably steamer [SS La] Touraine has arrived unharmed with ammunition and 335 machine guns.” Von Papen was being facetious. She had indeed sailed on February 27 from New York to Le Havre, France and caught on fire five hundred miles off the coast of Ireland on March 6. The New York Times reported the next day, “only the barest facts of the disaster on the Touraine are known, and there is no hint of the cause of the fire on board the vessel… A message from Queenstown said that the fire on the Touraine was ‘fierce.’” The fire had broken out in two separate cargo areas. French authorities at once suspected foul play. After a thorough investigation authorities identified a suspect who, as it turned out, had not caused the fire. Either way, von Papen’s superiors now had evidence that the sabotage campaign they had ordered was in full swing. The bomb maker had scored a first, documented success. All eighty-four passengers escaped unharmed. The cargo was ruined.

Thomas J. Tunney, head of New York’s bomb squad

Captain Thomas J. Tunney, who recounted his experiences in the war as head of New York’s bomb squad, detailed several mysterious fires on ships in January and February 1915. Tunney recalled that three ships, the SS Orton, SS Hennington Court, and SS Carlton caught fire without an apparent reason in those first two months of the year. None of these three ships made it into the papers and as a result could not be verified as the beginning of the bomb plot. Other ship blazes did enter the news: On February 7, the British freighter SS Grindon Hall caught on fire in Norfolk harbor. On February 16, the Italian steamer Regina d’Italia loaded with oil, kerosene, and cotton burst into flames at Pier B in Jersey City, New Jersey. The steamer’s destination was Naples, Italy. The fire destroyed the entire cargo. No reason could be determined other than that the conflagration started among the cotton bales in the forward hold. On February 29, the English freighter SS Knutsford loaded sugar in New York harbor when dockworkers found a cigar bomb hidden in a bag. The fire on the SS La Touraine, which sailed on February 27 from New York, has already been mentioned. On March 16, the Italian steamer SS San Guglielmo sailed from Galveston, Texas, “by way of New York” with six thousand bales of cotton. The ship made it to Naples but mysteriously caught fire as it docked there on April 11. The entire cargo burned, causing $200,000 in damages ($4.2 Million in today’s value).

Not only ships caught on fire. On January 18, 1915, two weeks after the sabotage order and five days after Dr. Scheele received his lead pipe delivery, a large steel mill of the John A. Roebling’s Sons Company in Trenton, New Jersey caught on fire and burned to the ground. Scheele’s lab was located approximately sixty miles from the factory. Roebling specialized in steel wires and produced anti-submarine netting and artillery chains for the Entente. Insurance companies estimated the extensive damage (without any loss of life) to be a staggering $1,500,000 ($315 Million in today’s value). The owners denied that the plant stored combustibles.

Dismayed with the pace of sabotage operations, and doubting the capabilities of Franz von Papen, the German admiralty decided to dispatch another agent on March 20, 1915 who took over the project. Franz Rintelen, the son of a banker in Germany, who spoke good English and had been in the United States as an apprentice would be the “Dark Invader.” The production of the cigars moved to the workshop on the German ship Kaiser Friedrich der Grosse and proceeded in earnest on April 13, 1915.

If the chief engineer of the Kaiser Friedrich der Grosse can be believed, agents placed ten bombs on each ship selected for destruction. Investigators of the New York bomb squad could only identify thirty-five ships, one third of the actual targets. This is not all. Fifteen more ships reportedly caught on fire, allowing for the suspicion that another fifty contained bombs. Cigar bombs even set the Canadian parliament in Ottawa on fire in February 1916. Multiple factories exploded in May, June, and July 1916. In the end of July, the grand prize, the largest loading dock for Entente munitions on Black Tom Island in the New York harbor, exploded. German agents had used incendiary devices to start the conflagration.

Serious fires severely damaged the American warship USS Oklahoma in the Camden, New Jersey, shipyards. A few weeks later two more U.S. navy ships mysteriously caught on fire in the Philadelphia navy shipyard. The government, obviously embarrassed about this string of “accidents,” never admitted sabotage. Despite the public denials, the Philadelphia Evening Ledger quoted government insiders in Washington as saying, “the fire on the Oklahoma strengthened the suspicion that the United States is being subjected to the hostile activities of partisans of the war in Europe.” The Oklahoma entered service with a year delay in 1916. She succumbed to flames and capsized in the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, taking 429 members of her crew down with her.

In addition to the navy yard fires, seventeen major fires authorities suspected as the handiwork of German agents occurred in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Maryland in 1915. Most notable were the explosions in the facilities of major producers of war materials for the Allies, all to the south of New York. Several munitions plants of DuPont, the Aetna factory in Grove Run, New York, Bethlehem Steel in the like named Pennsylvania town, the Baldwin Locomotive Company in Eddystone, New Jersey, A. Roebling and Sons in Trenton for a second time all blew up or caught on fire that year. The two consecutive fires that destroyed large portions of Bethlehem Steel’s production facilities caused celebrations in German pubs with toasts to the destruction of this hated company. In June 1916, a fire that likely started as a result of firebombs in Baltimore harbor, incinerated two steamers and caught the grain elevators on fire. The fire department estimated the damage to be over $2,000,000. In the summer of 1916, the prized jackpot of all targets blew up. Investigations in the 1920s and 30s traced the explosion to several German agents including Paul Hilken and Friedrich Hinsch. The Lehigh Valley Railroad Company’s loading terminal on Black Tom Island in New Jersey had so many explosives stacked in its warehouses and dock sheds that their combustion caused an explosion so powerful that it created an earthquake registering 5.5 on the Richter scale. It could be felt as far south as Baltimore, where the conspirators toasted to the success of their mission.

The Black Tom Island on the morning after the explosion

Dr. Scheele’s group did not escape detection. With the help of a German consular officer in Florida he escaped to Havana, Cuba in the beginning of 1916. Just a few weeks later, a U.S. Secret Service trap snapped shut. While eight other conspirators received stiff sentences, the American authorities assumed for the longest time that the chemist had made it back to Germany. Finally, in 1918, after letters between Dr. Scheele and his wife surfaced, American agents found him living under a false name in Cuba. In March 1918, Cuba extradited the agent. Scheele, fearing that he would be sentenced to death in a court martial, offered to switch sides. When chemists of Thomas Edison’s laboratories debriefed the doctor, the deal was done. They could not believe their eyes when the German agent showed all he knew. Abandoned by his government and branded a traitor, the “brain of the [firebomb] conspiracies” became an American agent. Until the end of the war he worked on multiple bomb designs, air propelled artillery shells, and a host of other inventions he had in his repertoire. His firebomb inventions became patents assigned to the United States Navy. Without ever having to serve a single day in jail, the chemist retired in Hackensack, New Jersey after the war.

It will never be possible to positively name every ship that the German sabotage agents targeted in 1915 and 1916. The group of saboteurs around Dr. Scheele freely admitted their crimes and put numbers to their efforts. The thirty-five ships the group stood accused of having firebombed can be fully documented. An added group of thirty-nine ships that also suffered highly suspicious fires in the same period brings the number of targets to seventy-four. Obviously embarrassed U.S. authorities downplayed and tried to hide the fact that German sabotage agents had breached navy yards in New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Five American warships suffered fire damages. The USS Oklahoma and USS New York, two new battleships in construction, were almost completely destroyed.

American, British, and French authorities found cigars on thirteen ships in the time between January 1915 and April 1916, most notably on the SS Kirk Oswald in Marseille on May 10, 1915. The Kirk Oswald was not the first ship where authorities discovered bombs. The SS Cressington Court, the SS Lord Erne, and the SS Lord Downshire all had bombs in their holds when they docked in Le Havre. The French government sent only the incendiary devices found in Marseilles to New York. Captain Tunney of the New York Bomb Squad used these bombs to uncover the entire plot.

Besides the reported incidents, a potentially much larger number of ship fires, in which the crews managed to extinguish the blaze, never made it into the news. There can be no doubt that the firebombing of ships and factories with Dr. Scheele’s cigars caused far more damage than previously thought. The man who could have shed light on the extent of his activities quietly lived in New Jersey until he took his secrets with him into the grave. He died on March 5, 1922 in his home in Hackensack, New Jersey, of pneumonia.

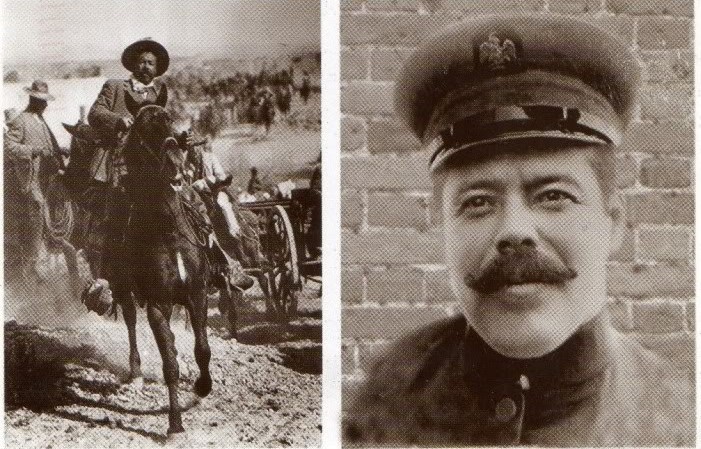

Felix A. Sommerfeld and Pancho Villa in 1914

Dear friends, I am proud to announce that after two years of hard work and negotiations, my second book on Felix Sommerfeld will be available in Mexico and the rest of the Spanish speaking world sometime next year. The title will be Felix A. Sommerfeld y el Frente Mexicano en la Gran Guerra. The publisher is Penguin/Random House. Thank you for your patience. I will be in Mexico several times in 2019. If you are associated with a university, school, museum, historical association, and you would like for me to come (always free of charge) for a presentation, an event, a book signing, please write me where and when, and we will try add the event into our schedule.

La Intriga de Huerta

Sommerfeld’s last record before he disappeared into mystery

Estimados lectores, me enorgullece anunciar que después de dos años de arduo trabajo y negociaciones, mi segundo libro sobre Félix Sommerfeld estará disponible en México y en el resto del mundo de habla hispana el próximo año. El título será Félix A. Sommerfeld y el Frente Mexicano en la Gran Guerra. El editor será Penguin / Random House. Gracias por su paciencia. Visitaré México varias veces en 2019. Si está asociado a una universidad, escuela, museo o asociación histórica, y me gustaría que viniera (siempre de forma gratuita) para una presentación, un evento, o un firma de libros, por favor, escríbame dónde y cuándo, e intentaremos agregar el evento a nuestro plan.

The circumstances of Russian election meddling in 2016 that brought Donald J. Trump into the White House with less than 100,000 votes tipping the electoral college show remarkable similarities to the “neutral” period of the United States 100 years ago.

When World War I started on August 1, 1914, the United States and Germany had a harmonious relationship. Trade between the countries had been increasing since the turn of the century. German chemical giants such as Bayer had invested in US production facilities. German lenses, chemicals, dye, and machines permeated American supply chains, American wood, copper, silver, and tungsten, fertilizers, as well as finished goods such as singer sewing machines filled the merchant marine steamers on their way back to Europe. Huge immigration from Germany to the United States between the 1860s and early 1900s solidly established German culture in the US, singing and drinking clubs, German language papers, German style beer were established in every major town.

When Germany invaded Belgium in September 1914 and committed well popularized atrocities, exaggerated in the pro-British press in the US, the relationship quickly soured. The German government received reports from its intelligence organization, the Secret War Council® in New York, that it was quickly losing the propaganda competition against Britain. Moreover, the British sea blockade and censorship of all transatlantic communication caused the United States to become an important supplier of war materiel to the Allies. Germany decided to counteract these developments. The actions that followed almost read like a playbook for Russian infiltration of the American political and economic life before and since 2016.

In 1914, the United States, despite declaring neutrality in the European war decided to allow J.P. Morgan to provide huge loans to the Allies and thus supply Germany’s enemies with American weapons, munitions and other war materiel. This decision against German interests led to serious repercussions. The situation today, the international relationship between the Russian Federation and the United States, is not much different. When the Soviet Union ended its grip on Eastern Europe in 1989, the understanding was that NATO would either incorporate Russia and expand into the former Soviet republics or leave the former Soviet zone of influence alone. While Russia went through significant economic and political upheaval in the 1990s, this understanding was broken. In 1999, Poland, Hungary, and the Czech Republic joined the organization, amid much debate within the organization and Russian opposition. Ten years later seven more Central and Eastern European countries joined NATO: Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Albania, Croatia and Slovenia. The most recent member state to join NATO was Montenegro in 2017. All this happened on the borders of the Russian Federation. When Ukraine and Georgia decided to apply for NATO and EU membership, Russia went to war. Not only militarily. Russian agents infiltrated western political parties, started psychological operations, and devastating cyber-attacks. The war between Moscow and the West has been in full swing since 2009.

Germany’s infiltration and attacks on the United States in 1914 and 1915 centered on three items: Propaganda, disrupting the production of war materials, and infiltration of the political system. German agents started a press office that funneled German-friendly articles to newspaper editors. In today’s world such a strategy would attempt to influence outlets such as FOX News, Breitbart and InfoWars. However, German agents not only influenced the opposition press. Articles and interviews appeared in pro-British (or at least not pro-German) papers such as the New York Times and Washington Post. Initially very successful was the disruption of America’s war industry. German agents managed to buy up all available smokeless powder for one year. They also bought all available hydraulic presses needed for the production of cartridges. Other agents bought and shipped munitions to Mexico and India to take them off the market for the Allies. While there is no indication that Russia is sabotaging the US economy, the introduction of psychological warfare is more palpable. In 1914 and 1915, German agents first sabotaged British shipments of war materials by organizing labor strikes and smuggling incendiary bombs into the holds of steamers. The labor strikes in the rust belt grew to such a fervor in the summer of 1915 that the Wilson administration had to get involved in mediation. Thank German funding of these strikes when you enjoy today’s 40 hour work week. Germans did not stop there. Agents infiltrated and financed the peace movement that favored a complete arms embargo for all combatants. German agents used people like William J. Bryan (secretary of state) as well as union leaders, senators, and local politicians to push their agenda. While suspicions existed, the detailed facts of the Secret war Council®’s work remained a mystery for 100 years.

Without question, the arrest of Mariia Butina shows the existence of Russian agents infiltrating political realms of the United States. Just like the German agent Felix A. Sommerfeld openly living in New York, openly associating with officials of the Wilson administration, even being asked on occasion to intercede in Mexico on its behalf, Butina operated in plain sight (the name of my first book on Felix Sommerfeld). Sommerfeld boasted to have tea with the American Secretary of War when passing through Washington. He passed information to the Secretary of the Interior, knew the head of the Bureau of Investigations (precursor of the FBI), and helped the American Chief of the Army, Hugh L. Scott, negotiate with Pancho Villa.

Photos exist with Butina interacting with leaders of the NRA, a former presidential candidate, and select republican operatives. If the parallels to World War I should give guidance, Russia’s psy-ops team includes agents in the Christian Right movement, White Supremacist groups, and influential people in the political public discourse. One of the most significant German agents in World War I was the chemist Walter T. Scheele and his former boss, the CEO of Bayer Corporation, Hugo Schweitzer. Both moved to the United States in the 1890s and remained on the payroll of Germany’s military as sleeper agents until activation in August 1914. Scheele became Germany’s bombmaker. His brilliant inventions of incendiary bombs sank or destroyed more than 75 freighters, blew up the New York harbor, uncountable factories and logistics installations. Moreover, his activities caused a mass panic in 1915 which bolstered powerful voices supporting the implementation of an arms embargo against Europe.

Today, we are witnessing the results of a successful psychological operation that likely is at the heart of only 40% of Republicans seeing any value in NATO membership, broad support for economic penalties against the EU, and a general hostility to immigration. All these developments are in line with Russian goals of disrupting the global international order, weakening the American political system, and negatively affecting bilateral relations of the United States with allies and economic partners. If World War I can be a guide, there will be years of investigations into the mechanics of the infiltration of a hostile foreign power into the American political and economic system. However, history also tells us that vigilance is key to protecting the American way of life. Agents such as Butina or Felix Sommerfeld are just the few operating in plain sight, the tip of a likely very significant iceberg. Read my award winning World War I trilogy, the Secret War Council, the Secret War on the United States in 1915, and Felix A. Sommerfeld and the Mexican Front in the Great War. You will be amazed how these books relate to today!

April 6, 1917 marks a day in World history that should not be forgotten: The United States of America declared war on Germany. The declaration of war followed years of German subversion of the US economy, politics, social fabric, and national security. When the war started in Europe in August 1914, Germany dispatched a group of secret agents to New York and activated sleepers and active agents already there. The leader of the group was an unknown bureaucrat who worked for the German Interior Department. He had been to the United States on a few occasions and spoke English well. In charge of the Secret War Council, Heinrich F. Albert was joined by the German Military Attaché and future chancellor of Germany, Franz von Papen. Von Papen’s job was to gather intelligence on munitions contracts the Allies concluded in the United States. Especially England was wholly dependent on US military supplies, as well as food and raw materials. Von Papen also provided German reservists with false passports to make it from the Americas to Germany through the tightening English blockade. Karl Boy-Ed, the Naval Attaché oversaw naval affairs, such as supplying the roaming remnants of the German navy in the Atlantic and Pacific and taking care of the thousands of stranded sailors in US ports. Since foreign intelligence was exclusively a naval affair, Boy-Ed also took over and ran the naval intelligence operation in the US and Mexico. Finally, the former German Minister of Colonial Affairs, Bernhard Dernburg, joined Albert in the beginning of September to assist with raising funds for Germany’s operations overseas and to counter the highly effective British propaganda in the US.

Heinrich F. Albert

While focusing on combating British, French and Russian activities in the US in the first months of the war, the United States became the main supplier of Germany’s enemies by 1915, thus a combatant in German eyes. Germany decided to threaten the supply lines from the United States with unrestricted submarine war, sinking not only allied by also neutral/American ships. When a German submarine sank the British liner Lusitania in May 1915 and almost provoked a US entry into the war, the Emperor curtailed the unrestricted submarine war until the US would be busy with its own affairs. To this effect, Albert financed, while Boy-Ed and von Papen organized groups of sabotage agents all around the US, setting factories on fire, sabotaging ships, and organizing labor unrest. This unfolded in the spring and summer of 1915 and culminated with the explosion at the Black Tom loading terminals in the New York harbor in the summer of 1916. German agents also supported factions fighting in the Mexican Revolution with American arms and munitions, first to restrict the market for the purchasing agents of the Allies, and by 1915 to actively provoke border incidents that would draw the US military into defending the US-Mexican border rather than potentially joining the Allies in Europe. These efforts culminated in Pancho Villa’s attack on Columbus, New Mexico in March 1916. German propaganda efforts, including the spreading of one-sided or false news, bribing editors of “respected” news outlets, and even purchasing a major daily in New York, supported the acts of war against the United States.

The German strategy had been to reinstate unrestricted submarine warfare as soon as the threat of an American entry into the war on the side of the Allies became unlikely. The summer of 1916 was the point at which the US was effectively neutralized as an active threat for the German Empire. A spy panic had gripped the country. The public saw daily evidence of German sabotage efforts, the rust belt was gripped by horrendous labor strikes, even the Republican candidate for the presidency Hughes was under suspicion of support by the Kaiser. The New York harbor lay in shambles, dozens of sabotaged neutral freight ships caused sky rocketing insurance rates, while the courts tried notorious cases against the few German agents, authorities managed to catch. Worse, the attack of the Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa on Columbus, New Mexico precipitated virtually the entire US military and reserve to fight in Mexico or secure the border. The country was effectively paralyzed.

Drawing of a German Pencil Bomb, used to set fire to ships and factories.

Yet, the German government did not follow through on its strategy. Divisions within the cabinet, especially the Navy and the Foreign Office, caused the Emperor to hesitate re-instituting unrestricted submarine warfare. This hesitation would have dire consequences. While in the summer of 1916, the US military suffered from a lack of preparedness, the Pershing expedition into Mexico as well as the call up, training and equipping of the US reserve quickly changed the situation. When in February 1917 the Kaiser finally agreed to the renewed submarine war, President Woodrow Wilson had the ability, the public backing, and a trained and equipped military to respond with a call to arms. The last member of the Secret War Council - von Papen and Boy-Ed had been expelled in the fall of 1915, Dernburg left voluntarily after the Lusitania sinking - Heinrich Albert, left with the German diplomatic corps in the spring of 1917. Prosecutors and historians never fully uncovered his role. He continued in German politics, became Secretary of Reconstruction in 1923, then became Henry Ford's man in Nazi Germany.

Rather than taking advantage of restricting supplies to its enemies, Germany had inadvertently strengthened the US to become its greatest nemesis. GIs began pouring into the battlefields of Europe and started to tip the balance of a stalled war. Even the separate peace, Germany concluded with the Russians could not change its defeat. Only two-and-a-half years after Pancho Villa attacked Columbus and German agents blew up the New York harbor, and one-and-a-half years after the US declaration of war, Germany sued for unconditional surrender.

If you are interested in the details of this story, read the Secret War Council® trilogy on the German Secret Service in North America between 1914 and 1917.

Sergey Kislyak, the Russian ambassador had meetings with top officials of the Trump Administration before the U.S. elections last November. What did the officials talk about with the ambassador? Is it standard procedure for political campaigns to engage with foreign government representatives?

Count Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff

Lessons could be learned from the Secret War Council's activities during World War I in the United States. The German government through its ambassador Count Bernstorff wanted to learn about attitudes of American politicians with respect to Germany, the German U-boat war, the peace movement, and the like. One of Bernstorff's goals was to find opposition to the Wilson administration which in effect could counteract American trade policies clearly favoring Germany's enemies. Wilson allowed American banks to extend huge loans to England and France through J.P. Morgan. One of the people who Bernstorff courted was Wilson's Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who strongly opposed these loans. He feared they would eventually pull the U.S. into the war, which indeed happened in 1917. Bernstorff also had close contacts with leaders of the labor movement, which were divided about arms and munitions sales to Germany's enemies. German-American lawmakers in Congress as well as senators and representatives with large German-American constituencies were on Bernstorff's short list for influence. So, are contacts between foreign governments, even if they are hostile, to American lawmakers normal? With respect to exchange of views and social interaction yes.

However, the German war strategy in the United States did not only involve the well-known and well-liked ambassador Bernstorff. Immediately at the onset of the war in August and September 1914, the German government sent a group of agents to New York to run the pro-German propaganda campaign, raise funds for cornering strategic industries, such as smokeless power (for munitions manufacturing), and chemicals needed for explosives. The German military ordered these German agents in 1915 to conduct sabotage operations against American factories, ships that transported munitions to the Allies, and logistics installations. This sabotage campaign caused tremendous damage to U.S. industries and Allied customers. German agents produced labor strikes in the rust belt so large, that only the implementation of a 40-hour work week quelled them. German agents also caused widespread violence along the Mexican-American border, culminating in Pancho Villa's attack on Columbus, New Mexico in March 1916. By the summer of 1916, literally the entire U.S. army and reserves were in Mexico or at the border to provide security and capture the Mexicans who had attacked the U.S.

What is important about these clandestine operations is that the German ambassador was widely suspected to have been in charge. He was not. In fact, he strongly opposed the sabotage campaign and other acts of war Germany was committing. We know today, that the German government used the Secret War Council in New York to run these missions. The ambassador knew about some of the operations but purposely tried to maintain plausible deniability.

Using the German example from World War I, it is likely that in the case of Russian election interference in 2016 Sergey Kislyak, the Russian ambassador, is not the person to look for. It is not likely that Russia used its ambassador for any more than information gathering, mingling with the political players of both the Trump and Clinton campaigns. Just like Bernstorff in 1915 and 16, Kislyak operates under the diplomatic mantra of plausible denial. The real agents are here in the United States but run under a different command and control structure. When Obama expelled a group of 35 agents and confiscated two Russian properties, he likely took out the modern Secret War Council. It is this group of agents, who conducted the election interference, hacking operations, and other yet unknown operations to throw the American political system into chaos. Any contact between them and members of the Trump campaign would be a completely different issue. Should these agents have found ways to synchronize leaks and misinformation with efforts of the Trump campaign to defeat the Clinton campaign, the Espionage Act of 1917, specifically instituted to combat German clandestine agents, would apply to anyone involved, including members of the Trump campaign.

Since the World War I example is especially fitting because German operations happened in a country officially at peace with the United States, the history of German clandestine operations in the United States between 1914 and 1916 might be especially instructive.

Yesterday, February 14, 2017 was a bad day for the government of the Russian Federation. One of their highest placed assets in the U.S. government was removed from leading the National Security Council after weeks of pressure from intelligence agencies and the Justice Department to do so. General Michael Flynn did not lie to the Vice President. He was told to lie to the Vice President. General Flynn did not keep contact with the Russian government, he was told to do so. No person in his position would travel to Russia in December 2016, a month after the election of Donald J. Trump under suspicious circumstances, without the approval of the president-elect.

Felix A. Sommerfeld (left) next to Francisco I. Madero. Also Allie Martin and Chris Haggerty, both journalists.

Flynn and Trump’s links to the Russian government have been the topic of many reports in the press during the presidential election campaign. The exposure of Paul Manafort as a close associate of the Russian backed Ukrainian president, who was expelled, forced Trump to let go of his campaign manager on August 20, 1016. Manafort is still under investigation in the Ukraine for receiving illegal payments. His role in the deposed government and the subsequent invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces and the annexation of the Crimean Peninsula is yet to be fully exposed. His and Secretary of State Tillerson’s ties to Russian oil interests are in the open, but not many people seem to care.

There are likely more Russian agents placed deep within the Trump administration. Their access to classified materials as well as their influence on pro-Russian policies of the administration is known only to U.S. intelligence agencies. Whether these agencies will reveal what they know is a matter of security for them. Indications of their caution are the withholding of classified information from Trump and his advisors, as well as carefully placed leaks to lead Congress and the Press in the direction of treasonous activity of the new administration.

In 2012, I wrote a biography of the German naval intelligence agent Felix A. Sommerfeld. There are many parallels of how this man ended up the right-hand man of the Mexican President to people like Flynn, Manafort, maybe others like Bannon and Miller who suddenly appeared in powerful positions next to the American president. Like Russia, the German government in 1910 did not know that Francisco Madero, an opponent of President Porfirio Diaz, would be able to capture the reins of power in Mexico. As a result, Germany placed agents like Sommerfeld with all leaders of the resistance, in case they should gain the upper hand in the upheavals. But Madero won, and Sommerfeld became his trusted advisor and head of the Mexican Secret Service. All access to the international press came through Sommerfeld. Not unlike Flynn, Sommerfeld controlled much of the information reaching the Mexican president. In Sommerfeld’s case, he tried to keep detractors of Madero’s regime away from the new leader. Flynn seemed to have filtered information to influence Trump’s opinions on Russia.

In 1913, President Madero died in a coup d’état that members of the old regime engineered with the support of a rogue American ambassador. Sommerfeld quickly moved to join the resistance against the putchists, again placing himself at the heart of the Mexican Revolution. Other German agents under Sommerfeld’s leadership monitored, even militarily supported several revolutionary factions, most notably those of Venustiano Carranza and Emiliano Zapata. Sommerfeld covered Pancho Villa and became his chief weapons buyer in the U.S. During World War I, when it became clear that the U.S. government had taken sides against Germany in 1915, Sommerfeld used his connections and executed the German War Department’s order to create a war between Mexico and the United States. I am not trying to tell the entire story of Sommerfeld and the German Secret Service in America during World War I. You can read that in my four books on the topic (www.felixsommerfeld.com).

The purpose here is to point out that well-placed intelligence agents of a hostile foreign government often appear in plain sight (the title of my first book on Sommerfeld). In hindsight, it appears almost unbelievable that they were not exposed. More shocking is the realization how much damage these people can do while active. Sommerfeld succeeded in the entire U.S. military and reserve save for one division protecting Washington D.C. fighting in Mexico or protecting the Mexican-American border in the summer of 1916. That was precisely the plan of the German government: Keep the U.S. military distracted and from entering the conflict against Germany in Europe.

The damage people like Flynn and Manafort have already caused to the international standing of the United States can only be estimated. At this point, only one month after the Trump administration took power in Washington, NATO is seriously evaluating ditching the United States and mounting a European defense force, Russia is firmly entrenched in Crimea and has reignited its military operations against Ukraine. The forces that fought on the side of the United States in Iraq and Syria (Syrian free army, Peshmerga, and several others) have been sold out to the murderous regimes of President Assad of Syria and Erdogan of Turkey. Russia has thus stabilized its foothold in this strategic region, while the U.S. has been expelled. In the future, receiving support from hitherto friendly Arab states will be next to impossible. Bellicose statements from the Trump administration allow the suspicion that the U.S. government is planning to challenge Iran to the point that it can be attacked. Just like destroying Iraq increased the regional power of Iran, starting a war with Iran will empower Syria as a Russian backed actor.

In the Far East, the United States has cancelled the TTP agreement, a strategic economic alliance against the expanding influence of China. While not perfect, it has been replaced with … nothing. The U.S. has ceded its influence in the entire region to China without gaining anything. Weakening American influence in Asia, Europe and the Middle East has created power vacuums to be filled by Russia and China.

Germany dispatched Sommerfeld and a few others to gain intelligence. It did not realize that an agent like Sommerfeld one day could be in a position to influence, even direct events in the North American region. It might well be the case that seemingly fringe elements in American politics like Manafort, Bannon, Flynn, Miller and others have been influenced, maybe even compelled with rewards of some kind to gather around a fringe candidate who might never win a presidential election, but had the power to seriously destabilize the U.S. political system. Spreading fake news, paying members of the press to report only one side all have been tactics of the German government in the U.S. in World War I. The Secret War Council®, Germany’s command center in New York, paid off journalists, even bought a newspaper, while subverting the peace and labor movements. The Wilson administration did not change course or fell, but it certainly had its hands full.

In 2016, similar efforts destroyed the Clinton campaign and propelled Trump into the White House. Russia now has intelligence assets placed deep and high within the U.S. executive branch of the government. Exposure has become a vital national security requirement, in the face of foreign influence designed to prevent it, in the face of corrupt domestic forces in Congress and elsewhere, in the face of people who can simply not grasp the severity of what is happening in this country. This has happened before. In 1917, the U.S. passed the Espionage Act to counter German clandestine attacks on this country. Thousands were caught, interned, and expelled. Our great grandfathers fought in World War I to make the world Safe for Democracy. Will we wait until we all must fight to protect this country?

During World War I, the German naval intelligence agent Felix A. Sommerfeld helped the fledgling German effort to counter a very successful British propaganda campaign. Eventually, the United States joined the war effort on the side of the British, not solely but certainly to a large degree as the result of the British success to divide the United States population, create a huge spy panic in 1915 and 1916, and create the sense of an emergency that only a military cooperation against Germany could resolve. Still today, historians are grappling with and often failing to differentiate facts from fake news and propaganda. When I researched my book, one of these facts that appears in virtually all histories on the time, is that the German sabotage agent Franz Rintelen spearheaded an effort to install the former dictator Victoriano Huerta back in Mexico. For that end, the German government supposedly made millions of dollars available. These, according to Barbara Tuchman, Friedrich Katz, Michael Meyer and others, came from Germany via Havana to New York. When I discovered the financial records of the German embassy and the entire North American spy organization, I was perplexed to find, that not only did this money exist, the German government actually supported a different plan for Mexico, one in which Huerta had no place. German agents indeed helped the U.S. authorities to dismantle the conspiracy and get the Mexican agitator arrested. Those were the facts.

The German propaganda chief in the United States 1914-1915

Where then did Tuchman and others receive their information? I looked at Tuchman’s sources and found a reference to a New York Times article. The first words of the article said: “Tomorrow the Providence Journal will report…” The facts that followed came from John Rathom, a British agent in charge of British propaganda in the United States and the editor-in-chief of the British owned Providence Journal. Maybe Ms. Tuchman did not know who Rathom was, maybe she ignored the first sentence of the article. Katz referenced Tuchman, Meyer referenced Katz and on it goes with a fake news item remaining in the public realm for 100 years. The use of propaganda of a foreign government in the United States to move the political environment towards its end, seems to be happening today. It might be well worth and enlightening to study what happened 100 years ago in this country. After all, the U.S. support of the Allies and the eventual entry into World War I had a far-reaching impact on U.S. and world history.

Sommerfeld identified four rules that govern successful propaganda:

Felix A. Sommerfeld, 1911

1) Limit access to information and control the message for each targeted channel.

2) Preempt an attack, line up the important players beforehand and win the argument.

3) Mold the message in such a way that the target audience understands it.

4) Control the message with surrogates who are beyond reproach.

The first act of war in August 1914 by the British was the cutting of the German trans-Atlantic cables and installation of censors for all transatlantic information flow. This brilliant move made it impossible for the German government to communicate with its embassy and consulates in the United States. All news from German or pro-German or neutral sources had to come through Great Britain, where censors eliminated anything that did not fit the propaganda goals of the British government.

German-Americans constituted the largest minority in the United States, although this group was not at all as cohesive as English propaganda made it out to be. German communities included those united the Lutheran church, the German-American Roman Catholic community, the Amish and the Mennonites, both of whom had anti-war leanings. Poor laborers, farmers, and craftsmen had to worry more about their daily bread than joining a confrontation with the pro-British American movement. Many immigrants from the lower classes in Germany had changed their names and integrated fully into their communities as Americans. German merchants and traders, especially in the west and southwest, often were integrated in a way that there was no palpable difference from the rest of society.

These groups could not take sides for fear of losing their customer base. Thus, the raw numbers of Americans who identified their background as German, paint a superficial and wholly inaccurate picture. The 1910 census reflects that 8.2 million persons named Germany as their land of origin, of whom 2.5 million had been born in Germany. In addition to the German communities, other minorities courted by German propaganda also had the potential of being perceived as disloyal to the United States: The Jewish community, in general, wanted Germany to win against Russia since Jewish citizens there had few rights and were persecuted. The Irish and Indian communities sought independence from England and, as a result, were generally supportive of Germany.

The British propaganda effectively stoked the fears that these huge minorities would rise against their country of residence. The American public swayed into doubting German-American loyalty over the course of the first year of the war. The German government understood clearly that the reality was different, but failed to assert the facts. Even before the war started, Ambassador Bernstorff had “[…] informed the Wilhelmstrasse that the majority of German-Americans were lost for the German cause as far as direct engagement was concerned.”

The British systematically disseminated messages among American papers through genuine journalists as surrogates, acknowledging the other side’s argument to give the impression of impartiality. Their intelligence services provided sensational news immediately when – sometimes even before – events occurred. The British operation combined restricting and controlling access to the news, and backed their reporting with thorough intelligence work. English propagandists exploited the realization that the American hunger for facts and sensation trumped any German efforts, even without a highly anglophile American press, public, and government.

Walter Nicolai, the head of the German Military Intelligence Service in World War I commented in his 1923 memoirs, that there was no intelligence link with the propaganda effort. “The ‘Press Service,’ which has often been, and still is, in Germany confused with the ‘Intelligence Service,’ first devolved on the General Staff after the outbreak of the War, because no government department had made any preparations for its establishment. The Imperial Government had not comprehended that without such a service even military operations were impossible […] Unlike her opponents, Germany had not at her command a political, economic, and military service of information concocted in co-ordinated fashion by the Government. She did not […] take any advantage of political conditions in enemy countries or influence the neutrals by means of propaganda […]”

Heinrich Albert seconded the spy chief’s analysis. He spoke to the same issue as Walter Nicolai, head of German military intelligence, noting in his diary in the winter of 1914-15: “The English have systematically worked long before the war, and especially in the first few weeks when German news was not available here, in order to malign us, and to paint a fake picture of us. We neglected both to gain sufficient influence, and to win the entire American people; the only means [for us to counter the English propaganda would have been] English printed news papers [sic], which would give the readers, and impregnate them without their knowing or noticing it, German ideas. A great neglect, that we do not own one, just now when the newspapers play such a big part...”

The media 100 years ago were newspapers and magazines. If it was hard then to fight targeted foreign propaganda, one can only surmise what a vast Internet, social media, television, and film can achieve for a skilled propaganda person. If you want to learn more about propaganda, sabotage, undue influence in politics during the years leading up to the American entry into World War I, check out my books, The Secret War on the United States, and The Secret War Council.

It started innocently. A factory fire in New Jersey at an anti-submarine steel cable manufacturer. Then another at a Dupont powder plant. Dozens more in the next twelve months. Rumors about German sympathizers possibly sabotaging munitions orders for the Allies. Mysterious fires on ships carrying war materials to England and France. A labor strike in Connecticut.

German sabotage agent and agent provocateur Franz Rintelen

Newspaper headlines in the spring of 1915 brimmed with ever new suspicions of what was going on. British propaganda fanned the flames of suspicion. Investigators tapped the phones of German officials in the US. Yet the results of the investigations were meager. Were the incidents terrorism? Lone wolfs or state sponsored? While the American public went into panic mode in the summer of 1915, sabotage agents continued their deadly work, most undetected. The war in Europe had spilled onto the shores of the United States. It took decades to prove that Germany was behind it. 100 years later, we finally have records that identify foreign misinformation campaigns and clarify the questions of who, what, when, why, and how.

2016 is not much unlike those trying days 100 years ago. A stabbing here, a pipe bomb there. Suspicions of all people of Mid-eastern descent, immigrant, resident, and citizen. The wars in the Middle East have spilled onto our domestic soil. Now, just like then, the United States is ill equipped to deal with terrorism in the homeland. We have a hard time identifying the potential perpetrators, we have to balance requirements of order with the individual freedoms granted in our founding documents. An insecure public is prone to foreign propaganda that fans the flames of suspicion, racism, and anti-foreign sentiment. British and German propaganda was then disseminated through the mass media of the day, newspapers like the Providence Journal (owned by the British) or The New York Evening Mail (owned by the Germans). Hundreds of editorial boards across the nation received bribes, misinformation, and planted stories to support the efforts. Does that sound familiar?

In my book, The Secret War on the United States in 1915, I have laid out the facts of a clandestine terrorism campaign that Germany organized, financed, and executed in 1915. Much of what I analyzed shows eery parallels to today, especially after we have now learned that agents of ISIS are operating in this country and are creating havoc. Who is behind this? Are there command and control structures of terrorists in this country? In 1915, US officials hopelessly underestimated the extent of the German operation on American soil. Today, investigators are struggling and the government tries to calm a nervous public. However, lone wolfs are rare and the explanation most often is the result of a dead-end investigation. If you read my book, you will understand the tell-tale sign of a multi-faceted, foreign terror campaign being unleashed on this country as we speak. No need to panic! But a need to learn from the past.